Higher Education ROI

The Higher Education Value Equation

“Price is what you pay. Value is what you get.”

—Warren Buffett

Calculated and Characterizing Value

As consumers, we’re faced with value calculations all of the time. We’re constantly being presented with products and their prices and making decisions whether over the course of months of deliberation or within seconds. We might shop for a new car for over a year, taking test drives and pondering trade-in values for our existing cars. In other instances we are comparison shopping based on price. Often at the grocery store we might compare the cost of one brand versus another, searching for the price that feels fair to us and making our decision from there—whether to choose Brand A, Brand B, or skip the thing altogether. In other scenarios, we’re just buying without considering the price because we don’t have much of a choice. If you’re at Disney World and your kid wants ice cream, you just pay for it because you may not be back soon and you want the day to be special.

Situations like these are too numerous to count but there is a common thread that goes through them all. When we encounter a purchase opportunity, some level of calculation is going on in our heads. Whether we decide in an instant or over the course of months, we’re performing a value equation. That is, we’re deciding whether something is worth it to us. A value analysis, simply put, is the reconciliation between what I pay for something and what that something delivers to me in return.

It’s often up to me to decide when that reconciliation makes sense and when it doesn’t. When I was a kid I encountered these situations while trading baseball cards. Between my friends and I we would constantly think about whether a card I was asked to give up was worth more or less than one I would get in return. Because we all liked different players, we all made different decisions and determined what was and wasn’t valuable to us. We each had our own personal stories about what constituted value to us.

As adults, we’re often looking at the value of things not just from the level of transaction value but investment value.. If I invest $100 in this mutual fund, what will it likely be worth to me in a year? If I buy this painting for $1,000, how much might I be able to sell it for in five years? If I buy this home at its current market value, will I be able to make money on it by the time I’m ready to sell it and downsize?

In these cases, we’re certainly thinking about the financial outcomes. The $100 investment in the mutual fund pays a nice dividend and I think it will appreciate. The benefits are tangible. Great.

The same goes for the painting. I think I can re-sell it on eBay a bit down the line and make 20% on its appreciation. But I also might really like the painting. It gives me enjoyment and pleasure when I walk past it every day. My wife likes it too. Because of these factors, this investment also has intangible benefits to it. Even better.

When it comes to the fictional home, it’s likely to appreciate. It’s also helping me to take a monthly payment I might be otherwise paying in rent and paying down the mortgage. I also get a tax deduction on the mortgage interest. And certainly I love the floor plan and the pool. The tangibles and intangibles are definitely there. But the house also is in a wonderful neighborhood near some great schools. It’s the biggest on the block and it was built by a well-known architect. This house gives me something else: it comes with status, a very powerful intangible benefit.

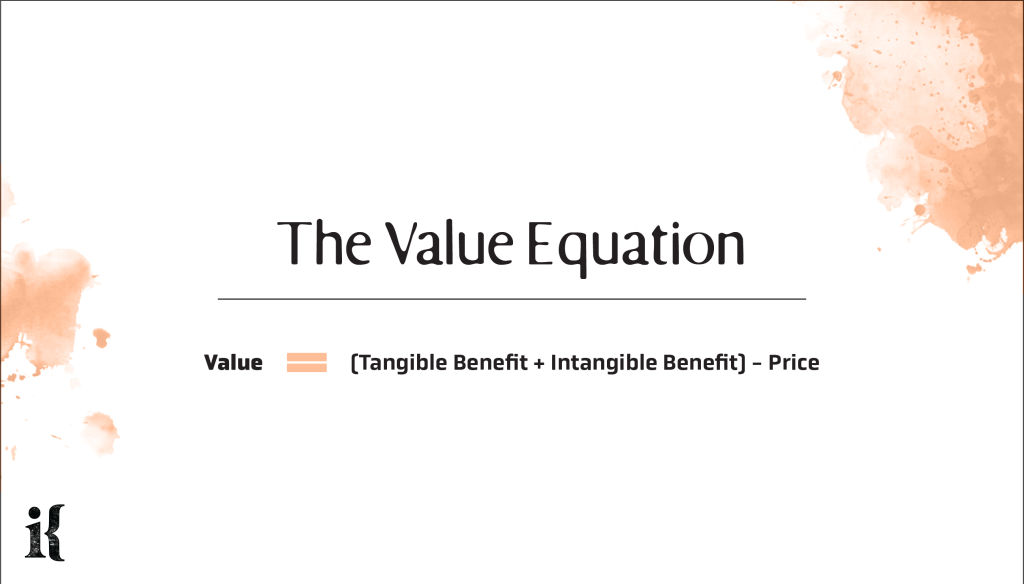

All of these illustrations are fictional but what’s happening is quite clear: when we buy something or invest in an asset, there’s a lot that goes on in our heads when it comes to placing value on what we get in return. And we all happen to be different. Some people consider a 2% yield on a mutual fund to be excellent while others would never touch it for that kind of a return. Some people have lots of concern about status while others care very little. In this context, we might further define a value equation to look something like this:

An equation like this is excellent when it comes to isolating what we get for what we pay, whether it’s a cold bottle of water on a hot day or new clothing for an important business meeting. But that equation may not tell the entire story because it frames the purchase as an individual transaction with seemingly short-term reconciliation.

A slightly different approach to the same scenario is to think about the purchase not as a transaction (conjuring images of a clerk at a cash register) but as an investment. An investment is strategic in nature and typically involves forgoing a small reward in the short term in favor in favor of a larger reward in the long term. A smart investment today, after all, can reap heavy rewards ten years down the road or more. And once one factors in the power of compounding, the size of that investment grows dramatically larger the longer the time horizon grows.

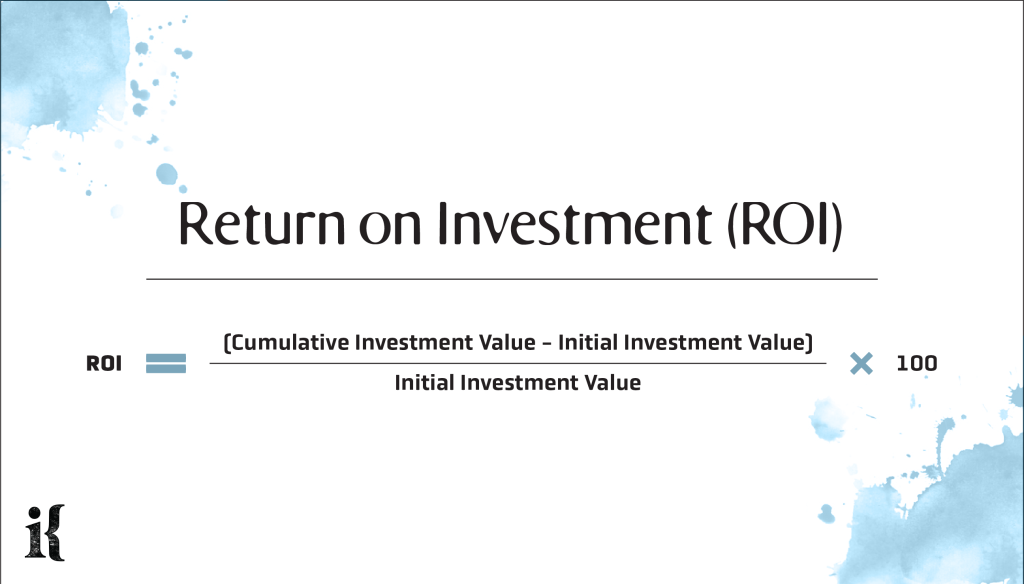

We call those rewards a return on that investment, typically thought of as what I gain in the long term from my initial investment in some vehicle or instrument. Commonly expressed as a percentage, return on investment (or R.O.I.) is calculated by subtracting the amount of the initial investment from its cumulative value and dividing that figure by that initial investment amount, multiplying that amount by 100. One way to express that formula is:

There are many nuances surrounding ROI that we won’t explore here, including different ways to approach the calculation. It’s not altogether perfect, either, because it doesn’t necessarily take into account the length of time that investment: a 5% total return in 2 years is better than a 5% total return in 3 years. That said, it is an important one to help characterize a short-term outflow as a long term investment vehicle with compounding returns. And, when expressed as a percentage, it helps investors to compare one investment to another: Investment A had a 12% ROI while Investment B yielded a 21% ROI. Those calculated returns, or measures of long term value, are yet another way that we all

Looking at value in this light can help any product marketer to think about how to talk about a particular offering. Because while we are all making these calculations in our heads when we consider purchasing things, we may not always be aware of what we might be getting in return. That’s where the marketer has an opportunity to step in and help.

Higher Education’s Value Equation

A purchase of any product or service typically involves a calculation of what it’s worth. If I pay for something I want to know what I get in return. Higher education is no different. If I am going to pay for a degree, I want to know what I’m going to get in return.

As previously described, there are myriad ways that we go through this calculation in our heads, but suffice it to say that there’s a cost a student pays and a host of benefits that student receives. On the cost side, we typically think of the primary cost as tuition: a degree’s sticker price. It’s common knowledge that most student’s don’t pay full tuition once financial aid, scholarships, and other award dollars are included. And then there are housing and meal costs, books and materials, fees, and a host of other outflows for a student to consider. A net calculation of all of that represents the degree’s price.

On the other side of the equation, there are all of the benefits, both intangible and tangible. In terms of the intangible, there is a wide variety of things to consider when receiving a degree. Perhaps they’re not talked about as much, but they’re highly valuable in life. These intangibles include:

- Personal fulfillment

- Life satisfaction

- Leadership and social skills

- Self-confidence

- Critical thinking ability

- Cultural awareness

- Expanded network

- Adaptability to change

- Communication skills

With regard to the tangible benefits, they typically come down to those that are financial in nature—either directly or indirectly. Some of the more obvious ones are:

- Earning potential

- Access to more employment opportunities

- Career advancement

- Job security

- Access to more employment benefits

- Eligibility for further degrees, certifications, and licenses

The sum total of these benefits can be thought of as the value the student gains from the degree. Pretty simple calculation, right?

While this equation is fairly simple when we stop to think about it, there is a substantial deficiency in terms of how institutions talk about this and help prospective students understand the value of that particular degree. Most institutions talk about tuition, certainly. And if you stop and think about it, most people talk about different institutions in terms of the tuition—the sticker price that most students don’t even pay to begin with: “Can you believe it costs $46,000 per year to go there?”

Institutions seem to forget that they can talk about the other side of the equation also—the benefits side. There’s an opportunity to talk about the many things that can be realized and frame the degree less as a transaction and more as an investment.

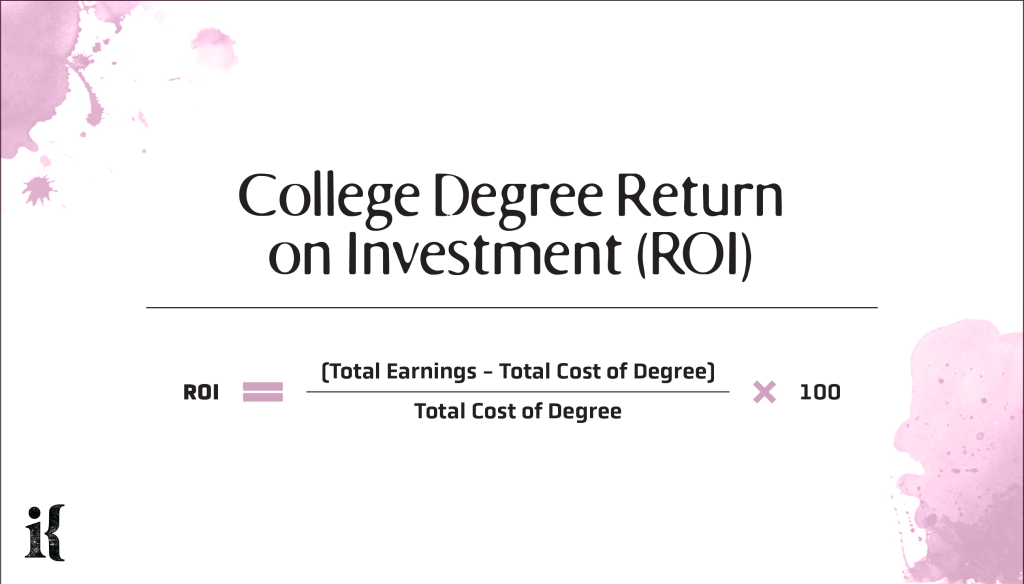

Borrowing from what we discussed about ROI in general terms, we can frame the purely formula for the value of a degree in the following form:

In this formula, “Total Earnings Increase” represents the additional money a student would expect to earn beyond expected earnings without a degree. This involves some estimation, certainly, but should give students a clear understanding of why the investment in a college education is a favorable one. Certainly the cost of college tuition is rising, but the value of that investment, even when just talking about the intangible benefits, is dramatic. According to a report by Georgetown University Center on Education and Workforce, individuals with a bachelor’s degree earn an average of $2.8 million over their lifetime, 75% more than those with only a high school diploma.

Like what you're reading?

Subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest insights in Higher Education and thought leadership.