Featured

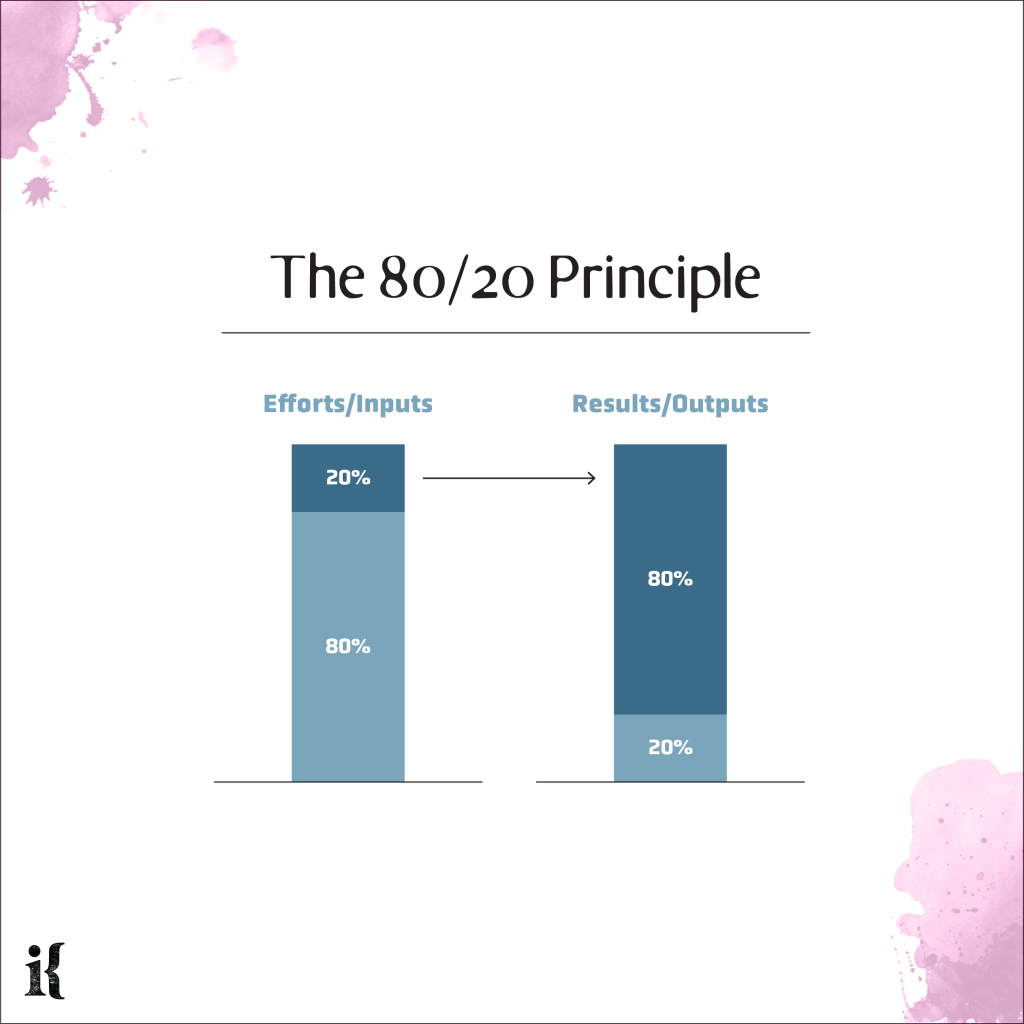

Understanding the 80/20 Principle

Introducing the 80/20 Principle

If you’ve ever taken a serious look at the carpet in your home, assuming that it’s been there for any length of time, you’ll likely notice that some parts of it are much more worn than others. You might notice that the areas of the carpet near your most commonly-used entry and exit door are much more worn, dirty, and matted down than, say, the carpet in your upstairs linen closet. Likewise, the carpet between the door to your bedroom and your bed likely have far more footprints and wear than, for example, the carpet in the far corner of your guest bedroom. If you did some rough measurements of these areas (assuming you were particularly bored) to measure the areas of significant wear versus those with little to no wear at all, you would likely realize that about 20% of your carpet’s surface area received 80% of its foot traffic and wear.

I can make this general assumption without ever stepping foot in your home because of a unique and thought-provoking phenomenon known as the 80/20 rule (or principle). The 80/20 is also referred to as The Pareto Principle because Italian polymath Vilfredo Pareto arrived at its truth in 1906 after noticing that 80% of the land in Italy was owned by 20% of the population. The work of Pareto and others ultimately discovered all sorts of instances of the notion that causes and outcomes are seldom linked on a 1:1 ratio but an 80:20 ratio. Alternatively it’s more common to discover that the relationships between inputs and outputs are disproportionate.

In his book The 80/20 Principle: The Secret to Achieving More With Less, author, entrepreneur and former partner with Bain & Company Richard Koch opens reader eyes to a myriad of scenarios where the “80 percent of results or outputs flow from 20 percent of causes”:1

- 80 percent of what you achieve in your job comes from 20 percent of the time spent

- 80 percent of outputs result from 20 percent of inputs

- 80 percent of consequences flow from 20 percent of causes

- 80 percent of results come from 20 percent of effort

- 20 percent of products usually account for 80 percent of dollar sales value

- 20 percent of customers are responsible for 80 percent of overall sales revenue

- 20 percent of your clothes will be worn 80 percent of the time

- 80 percent of a computer’s time is spent executing about 20 percent of its operating code

The examples go on and on.

It’s important to note that the 80/20 relationship is not meant to be an exact calculation, although that particular result is remarkably common. It’s not uncommon, though, for the ratio between inputs and outputs to be closer to 70/30 or even 90/10. Irrespective of the actual calculation, the spirit of the principle—that there is a disproportionate relationship between what causes and effects—is what is important.

There’s much we can glean from this idea as we think more and more about where it applies in the world and how we can leverage it. Understanding that 20% of our energy in solving problems goes an awfully long way (80% to be specific) should help us to examine and discover the specific nature of that 20%. Perhaps even more eye-opening, though, is the realization that the remainder of our energy—the leftover 80%—isn’t going very far at all. Compared to the high-performing 20%, the 80% is time and energy we’re basically wasting. And with the pressure to be as efficient as possible with resources, the 80/20 Principle is particularly important in higher education marketing.

1 The 80/20 Principle: The Secret to Achieving More With Less, Richard Koch, Currency, an Imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, 2017

Like what you're reading?

Subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest insights in Higher Education and thought leadership.